“Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life…” – The Very Reverend Dominic Barrington, Dean of York

On October 2nd, 2023, Ezzideen Shehab, a 28-year old Palestinian man, returned to his home in Gaza City, after studying medicine abroad for almost a decade – returned to his home with the great achievement, the great honour, of having become a doctor. That Friday night, the night of October 6th, 2023, his father prepared a feast. Writing about this joyous family gathering two years later, Dr Shehab remarked,

“We gathered as one family, laughing, speaking over one another, breaking bread with careless joy, pouring juice into glasses as though it were the wine of peace itself… My father’s hands moved as Christ’s once did, blessing the bread, dividing it among those he loved.”

In rapidly acquired hindsight, it was, of course, a fateful evening, and – precisely two years later, in October 2025, he recalled that “…somewhere, though no one could name it, there hung in the air that same fragile foreboding that filled the upper room in Jerusalem, when love spoke its last words before betrayal…”

For the very next morning, as we all know, the Middle East changed, as the world woke up to the horrific news of the Hamas attack on Israel that left over 1,100 people dead and some 250 more taken hostage. And that hideous betrayal of humanity was followed by nearly 700 days of military conflict – some two years of very unequal warfare during which another 1,700 Israelis and some 72,000 Gazans lost their lives, as the Gaza Strip was reduced to little more than rubble. Humans created in the image of God betrayed other humans created in the image of God, and love seemed to have been utterly vanquished from the stage.

It was not the context in which our young medical graduate had imagined that he would minister as a doctor. And over the next two years, his medical skills found themselves augmented by a spiritual – indeed, a theological – inner life, that led, three months ago, to the publication of the Diary of a Young Doctor – a record of his experiences and insights as he sought to live out his vocation in ever more desperate circumstances.

This profound reflection on living through what many have now termed a genocide contains many – too many – poignant encounters, such as the one he had on 27th May, 2025:

This morning, they came, two sisters. The elder, a girl, the youngest still a child. Nineteen and fifteen. They stood before me like two broken icons, hollow-eyed, limbs too light to hold the soul in place. I listened to their lungs wheeze and watched their hearts labour against emptiness. I gave them what I had: medicine, supplements – a gesture that felt almost obscene. Then the youngest, with her cracked voice, asked, “Doctor, how can we take medicine without food?”

I say this with tears on the page: I did not answer. Because what answer is there? … What is this world where children must beg for bread to take with their antibiotics?

And yet, as we hear this morning’s gospel ring in our ears, it is not hard to imagine those two emaciated sisters saying to Jesus, “How can we not worry about what we are to eat and drink?”… We seem to hear Dr Shehab saying to Jesus, “Look at this genocidal death and destruction – we are not of more value than the birds of the air…”

But, therefore… says Jesus… therefore, do not worry about your life…

It sounds a tall order – an improbably, perhaps impossibly tall order. If you read the doctor’s diary, you will realize that not a day passed in which he did not face his own mortality and vulnerability, as around him friends, family members and colleagues were killed and wounded indiscriminately.

And if it sounds a tall order to tell the quietly heroic Dr Shehab that he shouldn’t worry about his life, it feels, I suspect, an even taller order for us to contemplate, in the safety and comfort of the city of York, where most of us take for granted so many aspects of a secure life, the sudden deprivation of which would probably leave us extremely worried. But unless or until that happens, we may find it hard to hear or to understand Jesus looking us in the eye, and saying, therefore… therefore, do not worry about your life.

And it’s not the only thing which Jesus has been saying. Since last Sunday, when we heard the start of the Sermon on the Mount, in the well-known text we call the Beatitudes, Jesus has been fleshing out some of the implications of what it might actually mean to live out the values of the kingdom of heaven in the midst of the broken kingdoms of this world. And if we bother to take his teaching seriously, we cannot fail to be shocked and discomforted by the counter-cultural call to love and to give unconditionally, to work out where your treasure really is to be found, to forgive those who wrong us, to pray and to work for God’s will (not human will) to be ‘done’ – done right here on earth, and not just in heaven on a ‘pie in the sky when you die’ basis.

And – this morning – these counter-cultural teachings come to head in the verse immediately preceding what we just heard read, when Jesus says bluntly and clearly:

“No one can serve two masters; for a slave will either hate the one and love the other, or be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and wealth.”

“It’s simple,” says Jesus: “you have a choice… and therefore… therefore, make the right choice… and don’t worry about your life…”

And only a few years later, Paul, known to his Jewish friends as Saul, made the right choice. Indeed, you might say that for him, the choice became blindingly obvious, as he journeyed to Damascus on an errand that would have been emphatically the wrong choice. But newly commissioned by his extraordinary encounter with the risen Christ, Paul sets off across much of what was then the ‘known world’, manifestly not worrying about his own life.

And boy if he had been the worrying type, he’d have given up pretty quickly. Go look at some of his letters, and you can get a vivid sense of what it means not to worry about your life if you are intent on building the kingdom. In one particularly noteworthy passage, he says:

I am talking like a madman…with far greater labours, far more imprisonments, with countless floggings, and often near death. Five times I have received from the Jews the forty lashes minus one. Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I received a stoning. Three times I was shipwrecked; for a night and a day I was adrift at sea; on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from bandits, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers and sisters; in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, hungry and thirsty, often without food, cold and naked.

That is why, in our first reading, Paul speaks of creation being ‘subjected to futility’ – that is why he knows that the ‘glory of the children of God’ is a work in progress, yet to be fully realised, as we endure the groaning of the labour pains of a broken world that is only held together – that is only saved by hope… by the hope that in Christ (and only in Christ) can we be set free from ‘the bondage of decay’.

For Paul knew that the living out of such a hope can only be done in solidarity with the crucified one. Because one thing is utterly certain – there is no resurrection – there is no hope of resurrection – where there has been no crucifixion. And crucifixion is ubiquitous, as Dr Shehab realized when he encountered those two sisters in the ruins and rubble of Gaza: I tell you this. This is not war. This is crucifixion.

But it is the encounter with crucifixion, as the young doctor discovered, that we fully and properly learn to make the right choice:

I tell you: our humanity is not in question. It is crucified. And I, a doctor in Gaza, am merely one of many still clinging to the faith. Not because I believe will save me, but because I believe that suffering beside the innocent is the last honest thing a man can do.

On that fateful evening before the horrors of Hamas’ evil attack on Israel and all that followed, on that fateful evening, Ezzideen Shehab experienced the profound joys of a celebratory meal, gathered ‘as one family’, breaking bread ‘with careless joy’, recalling Christ’s own actions sharing broken bread and the ‘wine of peace’ ‘among those he loved’.

As we share in Christ’s celebration around that altar in a few moments, we are called to do so with an equally careless joy… but a joy that connects us with a saviour whose scars tell us of the cost of making the kingdom come on earth as it is in heaven:

“…if God still watches, let Him bear witness. For if He is silent now, then one day He must speak. And when He does, He will whisper not in Hebrew, nor Arabic, nor English, but in suffering. The only language that was ever real.”

Which is why, if we truly seek first the kingdom of God and God’s righteousness, if we are serious about praying the prayer which Jesus taught us, then, in fellowship with that young doctor, in fellowship with Paul, and with all who have followed the Crucified One, it’s time to stop worrying about our life.

Amen.

Dr Shehab still runs the Al-Rahma Medical Clinic in northern Gaza, offering medical care without cost, treating the best part of 500 people each week. If you wish to support his work, you can do so at https://chuffed.org/project/117739-dr-ezzideen-shehab

“He has spoken to us by a Son” – The Very Reverend Dominic Barrington, Dean of York

“Long ago God spoke to our ancestors in many and various ways by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son”.

Those of you with memories able to stretch back to the winter of 1979 may recall that the darkness and gloom of that December was brightened by a chart-topping release from the legendary Swedish group Abba, then at the very height of its popularity. Echoing Martin Luther King’s famous rhetoric from the March on Washington of 1963, they claimed, “I have a dream…”

However, unlike Dr King’s dream, which was rooted in a vision of action taken by humanity – rooted in the vision of white and black children being brave enough to join hands and proclaim justice and liberty together – unlike Dr King’s dream of humanity in action, Abba’s dream focused on different beings: “I believe in angels / something good in everything I see / I believe in angels / When I know the time is ripe for me I’ll cross the stream / I have a dream.”

I was reflecting on the difference between angels and humans, as I pondered the opening of the letter to the Hebrews a few days ago, while being driven alongside the River Jordan, journeying south through Israel and the West Bank from the Sea of Galilee to Jericho, and thence to Jerusalem. In Biblical times, the Jordan was a substantial, fast-flowing river, but the demands of agricultural irrigation in modern times has reduced its grandeur, and it can sometimes look little more than a stream – albeit a stream which still serves as the eastern border of what Joshua would have regarded as being the ‘Promised Land’.

In our first reading, of course, the ‘stream’ was so abundant, it being ‘the time of harvest’, the Jordan is actually bursting its banks, making the idea of crossing into that Promised Land something of a challenge – at least, a challenge for those who cannot face getting wet. And so, just as he did at the very start of their journey, some forty years previously, God parts the waters. And Joshua, and the Ark, and the priests, and the entire nation ‘crossed over opposite Jericho’ – crossed over on dry ground – to start a new existence – a new life, as the People of God… and, if they had lived out that vocation properly, that might have been the end of the story.

But as you turn the pages of the Hebrew Scriptures through the books of Samuel and of the kings, and as we read the words of the great prophets, we are reminded of the sinful nature of humanity, and of the failure of the Israelites to live up to their side of God’s covenant with them – a failure which, so the writers and the prophets make clear, ultimately leads to the destruction of the kingdom of Israel, a bitter exile, and a sense of alienation between God and God’s people.

Which – to cut a long story very short – which is why our second reading begins with the words, Long ago God spoke to our ancestors in many and various ways by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son.

Because the dream had failed. The dream had been betrayed. The inherent sinfulness and self-centredness of humanity had destroyed the dream that had led to that crossing of the stream by Joshua Mark I. That is why it was time to dream again. But to dream a dream that forsook the ‘many and various ways’ of the past – a dream that no longer relied on angels or messengers. A dream in which, in effect, God said, “this time it’s personal…”

Which is why, of course, he was named Joshua. Because the Hebrew name Yeshua – which in English we say as Joshua and which simply means ‘the Lord saves’ – the Hebrew name Yeshua, when it was translated into Greek, became Iesous, and in English, of course, that becomes Jesus. But tonight, when we mark again the beginning of ‘these last days’ in which God has ‘spoken to us by a Son’, we recognise that this Son is none other than Joshua Mark II – the new Joshua, setting out to recreate a great dream, and this time, doing it properly.

Which is why Joshua Mark II makes just the same journey as Joshua Mark I. If you read the account of Jesus’ baptism in the Fourth Gospel we discover that the precise place John is baptizing is not actually in that fast-flowing river itself, but in a place called ‘Bethany beyond the Jordan’ – a tributary rather like a railway siding, connected and adjacent to the river, but just on the eastern side of it, from a Biblical perspective – just ‘beyond’ it, in what is now the Kingdom of Jordan – right across from Jericho, exactly where Joshua Mark I had come to the river so many centuries previously.

So Joshua Mark II follows the steps of Joshua Mark I to the river. But there the similarity ends. Because Joshua Mark II is not going to command the river to stop flowing in order that he might pass through on dry land. The first people of Israel liked God to keep them dry, but Jesus founds the new Israel – the new people of God – by being plunged (the meaning of the word ‘baptize’) into the river at the hands of John. By being submerged as he crosses the stream, so that he might start afresh, and reconstitute a new Israel whose very foundational identity is tied up in a rebirth that confronts the depths, rather than avoiding them. A new Israel whose very mission – whose dream, if you like – is about a righting of the wrongs of human sinfulness and self-centredness, about proclaiming justice and reconciliation… about living out a love that is uniquely costly in its self-sacrifice.

The dream of the founder of the new Israel, the new People of God… the dream of Joshua Mark II goes beyond the ‘fairy-tale’ of Abba’s stream-crossing at the hands of angels or messengers. For in Jesus, as the author of Hebrews makes all too plain, God does this himself. And God doesn’t tip-toe around the dry edges of the stream – God wades right in, to inaugurate a new reign of justice, of mercy, of righteousness and love.

And if the body of the one we call the Christ could do that, then we, who, through our own baptism lay claim to being the Body of Christ – we, too, are called into the deep waters of God’s real purposes for God’s world – a fact that was most certainly not lost on Dr King, whose 97th birthday would be this coming Thursday, and whose dream immersed him in the pursuit of a righteousness ‘like a mighty stream’.

Dr King knew that, while angels have their place in God’s universe, sometimes God’s mission and purpose needs the commitment of those who are not just messengers, and he entered the deep waters of that call, even at the almost inevitable cost of his life in a United States that was still deeply segregated in terms of its economics, its housing and its education policies.

Today, as we recall the baptism of the Anointed One we learn is none other than Yeshua Mark II, and therefore as we recall our own baptism, the only question is whether we can stop shillyshallying around the edges of the water and wade right in, whatever the cost.

Amen.

“What then are we to say about these things?” – The Very Reverend Dominic Barrington, Dean of York

During half term, with my family, I visited the Anne Frank House in the centre of Amsterdam. Our visit was at the end of the day, pushing into the evening, but the crowds were still substantial, as we made our way slowly around this otherwise unremarkable house in which Anne, her parents and elder sister, and four other Dutch Jews hid out of sight of the Nazis for some two years, prior to their arrest in the early August of 1944.

In each of the rooms, the excellently curated information on display contains quotations from Anne’s now famous diary, creating an almost unbearable sense of poignancy as you immerse yourself in the story of those terrible times. Her youthful naivety and profound sense of hope is palpable, and all the more moving in the light of her eventual fate in the disease-ridden huts of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

My wife, my teenage sons and I were pretty silent by the end of our visit – and we were not alone. Despite the exit of the exhibition containing the inevitable café and gift shop, the atmosphere was muted and subdued. Being brought face to face with the horrors of the Holocaust made personal in such a very particular – and in some ways, very unremarkable – setting, it was as if we were all, inwardly, echoing the words which we just heard from Saint Paul: What then are we to say about these things?

Anne, of course, would not have been silent. Her answers to that rhetorical question fill her extraordinary diaries. “It’s really a wonder that I haven’t dropped all my ideals, because they seem so absurd and impossible to carry out,” she wrote, “Yet I keep them, because in spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart.”

And, of course, that goodness of heart is one of the things that, today, we gather to remember. The sacrifices of so many, especially in the two world wars, who rose up to fight against those who sought to dominate and subjugate others through acts of intimidation and violence and warfare. The thousands upon thousands who gave their lives to ensure freedom and peace for others. That sacrificial generosity should never be forgotten.

So it is, indeed, good that we should speak of ‘these things’ – that we should know what to say about them. For such sacrifices should inculcate in us, and in those who come after us, a similar desire to live out such radical generosity, and demonstrate that Anne Frank was not wrong about the fundamental goodness of humanity.

But that is no longer enough. When Paul demands of us to speak about ‘these things’, there is more to say. For if we talk for just a few more moments about the Holocaust, then we should note that, despite the 1.2 million visitors that come to the Anne Frank House each year, in Anne’s native Holland, a recent survey showed that 12% of Dutch adults believe the Holocaust to be a myth, or to be very greatly exaggerated. And if you focus on those under 40, that figure rises to 23%.

In Britain, the same percentage said they had never heard of the Holocaust, or – at best – knew very little about it, and over half were unaware that it resulted in the death of six million Jews. The figures for the United States are even more alarming.

More broadly, over 40% of British adults surveyed could not answer correctly which country was the principal enemy of the Allied forces, and over 50% did not know what the D Day Landings were. That, to my mind, suggests that our communal attempts to do some ‘remembering’ are not working as well as they should – and the consequences of this failure are alarming.

Writing in today’s Observer, the distinguished British historian Sir Anthony Seldon, powerfully recalls the optimism of the post-war government of Clement Atlee, who sought to deliver ‘a new Jerusalem’ for the people of Great Britain. https://observer.co.uk/news/opinion-and-ideas/article/in-1945-we-said-never-again-yet-already-weve-forgotten

Seldon contrasts it painfully with the reality we experience today, writing:

Unemployment, ill health, homelessness and despair are reaching levels that would have shocked the architects of the new Jerusalem. Nigel Farage’s Reform party has a credible chance of winning the general election due in 2029. Abroad, we see Europe divided and at war. In Germany, [the far right populist party] Alternative für Deutschland achieved its best results, with 21% of the popular vote. Far-right parties are performing strongly in France, Italy, Austria and Belgium. Russia is intent on beating Ukraine, and is shamelessly destabilising Eastern European countries.

In short, to summarize Sir Anthony’s words, the world feels as if it is an ever more dangerous place, despite the fact that we ought to know better. All of which says to me that we are not doing this ‘remembering’ thing properly. All of which says to me that we are not using our memories. Or, to put it in the language of St Paul, we have not come up with a proper answer to his blunt question that opened our second reading, when he demands of us What then are we to say about these things?

If you were to open your Bible and glance back at Romans Chapter Eight, from which we have just heard, you would find Paul explicitly addressing what he calls ‘the sufferings of this present time’. But he is clear that for God’s children, present-day sufferings do not diminish the hope of our calling – our calling to change the world, our calling to make the world a better place, our calling – like Atlee – to build ‘a new Jerusalem’ fit for a people committed to peace and justice. And Paul, as we heard, is clear that if we strive to do this, then nothing in all of creation ‘will be able to separate us from the love of God’.

But that’s only going to happen if we start remembering properly, and using our memories to fulfil that vision. Sir Athony reflected on the celebrations this year of the 80th anniversary of the ending of the Second World War:

We have … forgotten the lessons of the second world war. This summer, on the 80th anniversary, the bunting came out, books were published and war films and documentaries were shown. It felt cheap and vulgar. We were remembering winning a war, not why the war had been fought.

And with that forgetfulness, we find ourselves incapable of knowing how to answer Paul’s demanding question: What then are we to say about these things?

When the young Alice of Lewis Carroll’s Victorian children’s novels steps through the Looking Glass, she encounters the White Queen – a confused and confusing individual who explains that she lives ‘backwards through time’, as a result of which, she has a memory which ‘works both ways’. And when the bewildered Alice explains that she is unable to remember things before they have happened, her new friend exclaims, “It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backward.”

Whether Anne Frank knew Lewis Carroll’s books, I have no idea, but she would, I am sure, have agreed with the White Queen. For Anne was clear that, in her own words, “I want to go on living even after my death” – a fate that has been amply fulfilled by her remarkable diaries. Fulfilled, because her diaries that chronicle her memories of this most awful period of human history have been shared across the globe in every generation since those darkest of days. Shared, in the hope that we are called to realise, the hope that such terrible times could nor arise again.

But we will only be able to do that if we can work out, as Saint Paul demands of us, What then are we to say about these things?

And if we are serious in sharing Paul’s belief that the ‘sufferings of these present times’ can make us ‘more than conquerors through him who loved us’, then we need to make our memories work forwards, and not just backwards. For to do anything less is to dishonour those whom we remember today. And then we might, just possibly, start to change the world to be more Christ-like – to achieve that vision of ‘a new Jerusalem’. For as young Anne said in one of her last recorded remarks, “How wonderful it is that no one has to wait even a minute to start gradually changing the world.”

Amen.

“This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you” – The Very Reverend Dominic Barrington, Dean of York

There is peace (or rather, there is an absence of war) in Gaza. As of this past Friday, an agreement brokered by President Trump has garnered sufficient agreement from both Hamas and Israel that the guns have fallen silent, the bombs have ceased falling, the remaining hostages are due to be released, and thousands of Palestinians are returning to the areas of Gaza in which they once lived, to try and rebuild a new existence out of the ashes and rubble of their former homes.

Netanyahu has claimed that this is a ‘national and moral victory for the state of Israel’, and it would not be surprising, before long, to find a similarly outrageous claim from the leadership of Hamas, also suggesting that they have achieved some kind of victory. Which is why, at times like this, we probably get an understanding of how the Middle East could produce a poet who could utter such a statement as “Blessed be the Lord my strength, who teacheth my hands to war, and my fingers to fight.”

Of course, we are only matter of a few days into this ‘absence of war’ in Gaza. We have not remotely reached a condition that could genuinely be called ‘peace’; for now, we merely have a ceasefire, and a ‘peace deal’ is still a considerable way off, demanding more complex negotiations and discussions which could – so very, very easily – unravel, possibly plunging the region back into warfare and violence. To use the language of Jesus which we heard in our second reading, although we may well have some ‘fruit’ to celebrate this weekend, it is, by no means, ‘fruit that will last’, though we all hope and pray so fervently that this will, please God, eventually prove to be the case.

And for that to be the case – for this fragile ceasefire to turn into a lasting peace – people are going to have to stick at it. On both sides of the terrible divide which has become such a gaping chasm between Israelis and Palestinians, in both communities, and at all levels, people are going to have to stick at it.

People are actively, deliberately, and painfully going to have to embrace the costly work that will be necessary to ensure that real peace is achieved – the kind of peace that is about mending what is broken; the kind of peace that is about creating safety; the kind of peace that is about restoring justice; the kind of peace that, ultimately, might speak about and demonstrate something of the love of God – about which we find Jesus talking at the opening of our second reading.

Which is also, of course, what Nehemiah is trying to do, in that convoluted narrative which formed our first reading.

To refresh your memories, we are in the middle of the fifth century before Jesus was born, getting on for a century after some kind of peace had returned to Jerusalem following its sacking by the Babylonians in 587. The destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians then would have born some comparison to the destruction of Gaza we have watched in these past two years: just about everything of importance had been raised to rubble. The Babylonians were harsh and cruel conquerors, and once the Temple had been destroyed, pretty much everyone of significance had been led into a demeaning exile in an unwelcoming foreign land.

But super-powers come, and super-powers go, and after some fifty years of exile, the Persians topple the Babylonians, and their control over the ancient Near East was very considerably more benign. Those Israelites who wished to return home were allowed to do so, and, indeed, money was made available to them for the rebuilding of the Temple and of the city of Jerusalem.

But – despite the good intentions of the Persian king Cyrus – this was not entirely straight-forward. Apathy, corruption and self-interest meant that the reconstruction of the Temple was not, in fact, quite such a high priority as one might have expected should be the case. And our first reading finds us the best part of a century later, and Jerusalem is still a mess. It is still not the ‘vision of peace’ that is the meaning of its name. And the pious Nehemiah has been given support and permission by the Persian king Artaxerxes (for whom he is the royal cup-bearer) to return to Jerusalem and try and resolve the situation – and, in particular, to rebuild the walls around this once-great city.

And when we hear the talk of the city wall, we should understand that this is about more than defence. The city wall is profoundly symbolic of the rebuilding of the identity that the Israelites are, uniquely, God’s people – God’s children, called by God into a particular and loving relationship.

But those around Nehemiah do not want this to happen. The provincial governor, Sanballat; the leader of the neighbouring Edomites, Geshem; and the well-connected Ammonite, Tobiah; these three throw distraction, deceit and downright danger at Nehemiah to prevent the fulfilment of his great vision – but, as we heard, all to no avail. Nehemiah is out to bear fruit – fruit that would last a good long while. Fruit which could speak to a true ‘vision of peace’ that befits those whom God has called to be God’s people – people called to love one another, just as God loves us.

Nehemiah discovered the profound truth to which Jesus gave voice nearly five hundred years later that one can be hated by the world for doing what we might think of as God’s work. And, in Christ, the challenge of that work is, perhaps, a little more wide-reaching than Nehemiah would have perceived or understood.

For, in Christ, our understanding of being God’s children or God’s people has been transformed into a bigger picture – into the biggest picture that it can possibly be. For the special relationship with God of the old covenant, rooted in a religious understanding related to a specific ethnicity – that covenant has been broadened and replaced by one that neither knows nor recognizes any distinctions or barriers, whether to do with ethnicity, creed, colour, gender, sexuality, or anything else which can be used to divide one beloved child of God from another.

And the kind of love that in Christ we have received, and which we are called to share – the kind of love which will, truly, bear the fruit that lasts, that endures, that remains – this kind of love is generous… some would say generous to a fault… for it is, as Jesus remind us, a love that is ultimately rooted in self-sacrifice.

The opening of Psalm 144 may well jar in our ears, and it is a reminder that there is a militaristic vision in some of the older parts of the Hebrew Scriptures. And it is probable that in some shape or form much of this psalm has its roots in material similar to that found in Psalm 18, another, longer, psalm with much similar language about victory in battle – a psalm that is one of the older ones amongst those 150 beloved hymns of the Israelite people.

But this evening’s psalm, although it starts with hands that make war, and fingers which fight – tonight’s psalm changes gear, and its final four verses, give it a much later feel than the older psalm to which it is so clearly related. For in these final four verses we find a ‘vision of peace’ that has turned its back on war and violence. For they offer a vision of peace in which nobody is led into captivity, nobody need complain, a vision of an abundant life in which every need is met, and every person can be described as blessed.

That comes about – and, I suspect it only comes about – when people love one another as we have been loved by God in Jesus, living sacrificially, whatever the cost. If Israel and Hamas can learn a little of the dedication to God’s people and service that motivated Nehemiah, and which was seen, fulfilled in the life of Jesus… if those in the Middle East, and all of God’s children, here right now, and around the world… if we can all learn a little more of what it means to ‘love one another as I have loved you’, then we will bear that fruit that was so precious to Jesus – the fruit that will last.

Amen.

“I received mercy… making me an example to those who would come to believe.” – Dean Dominic’s sermon from St George’s Cathedral, Cape Town

The question – I think – the question which stares us in the face from this morning’s gospel is, “Are you crazy? Are you crazy?”

But before we work out the answer, may I first thank Dean Terry for his very gracious invitation to share this pulpit with me, which is an honour and a privilege. I bring you greetings from York Minster – and from our own Archbishop, Stephen Cottrell, the Archbishop of York. As some of you may know, for the best part of twenty years, our two dioceses have had a companion relationship, and it is a joy that Canon Maggie and I are able to represent that relationship this morning.

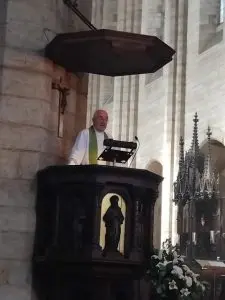

- Dean Dominic preaches from the pulpit at St George’s, Cape Town

- Dean Dominic pictured with Dean Terry and Canon Maggie

- A ‘God Bless Africa’ banner on display in St George’s Cathedral

But while it’s a joy and a blessing to share in this act of worship with you today, I’m still worried by the question – because I hear our readings shouting at me, “Are you crazy?”

Because today’s gospel is about utterly irrational behaviour. Today’s gospel is about doing things which make no sense at all. Doing things which are economically ridiculous, and which – to someone with a diary that is full to over-flowing with tasks that should have been done yesterday and meetings that must be attended tomorrow – things which are simply a waste of time. Today’s gospel is about being crazy.

This morning’s gospel is crazy, because the wilderness is a dangerous place. After all, it was in a wilderness that Jesus found himself spiritually wrestling no less a figure than the devil himself. And in a dangerous place like that you do not simply abandon 99% of your assets, whimsically to go off to find the one that has gone missing. I’m afraid the missing sheep – and, indeed, the missing coin – that’s just an asset you write off on the balance sheet of life. It is not something which – if you are sane, or rational, or efficient, or competent – if you are anything other than crazy – you just forget about.

After all, they tell us that time is money, and so many of us have far too little time to do the things that we even want to do. So not only would it be a crazy waste of time to go looking for that sheep, or that coin… it would be just as crazy to drop everything and run off when your neighbour summons you to an impromptu party they’ve decided to throw – something just to celebrate their craziness.

Let’s be honest. This is how real life works, isn’t it? This is the life that I find I have to I live if I’m going to survive the pressure of work, and family life, and all the rest of it. I don’t have time to be crazy, I don’t want to be crazy – at least, that’s what I find when I find myself looking in the mirror, let alone in my diary, or – when I dare to do so – in my conscience, or my heart.

Even today, some people look up to clergy, and I hope they find in me an example of someone who is rational, and ordered, and in control, somebody who is capable of running a very big cathedral with an awful lot of staff and worshippers and visitors and tourists… I hope they think I’m a good example.

And then that little voice pops the pin in the balloon of my smug, self-satisfied condition, and I hear that man saying to me again what he’s always said, when I quieten down enough to listen (which is not as often as it should be). And that voice says, “Are you crazy? Dominic – are you crazy?” Or, in the words of our gospel this morning, “Which of you does not go after the one that is lost…?”

And that is why I am so lucky – why we are so lucky – why we are so blessed to come to church this morning, and to discover we seem to be surrounded by some really crazy people.

Take St Paul. He’s a pretty frequent visitor to church most Sundays. Look how crazy he was. He knew all about the demands of what you and I probably call ‘real life’. Especially back in the day when he was more usually known as Saul – he knew all about that. He knew what tasks had to be done (mainly arresting these crazy followers of some jumped-up nobody of a rabbi from the north), and he knew just how to go about doing that. He was busy, he was capable, he argued really well. He had it all in hand. Until something crazy happened – something crazy which threw him off his horse, dazzled him with a light brighter than anything he’d ever known before, and gave him a new, crazy, outlook on life. And it was catching…

Paul’s new craziness was really catching. Because, if we are going to be honest, for many years Biblical scholars have been telling us that it is highly unlikely that the person who wrote One Timothy was actually Paul himself. Now, if you go to a university today and make false claims about authorship, and you’ll be out on your ear on a charge of plagiarism before you can snap your fingers.

But back in Biblical times, having your disciples attempt to echo your thoughts and what you stood for after your death – that was the highest praise. And so, someone – as I say probably not Paul, but one of those who had ‘come to believe’, because in Paul they found someone who was a really good example of how to live life – someone who had been touched by Paul’s craziness – someone else got it. And they used Paul’s name and identity to keep his ideas alive, and that someone else starts talking, in One Timothy, about how good it is – what a good example it is – to be crazy.

And so this morning, this shadowy author is speaking to us about how grateful he is that God strengthened him – strengthened him to be able, also, to live a crazy life, to be an example to others… To others who might find themselves needing to find a lost sheep or a lost coin when the rest of the world is saying, “No, no, no – be sensible. Don’t bother about that. It’s not the effort.”

And the story of Christianity, and the story of the Church of God – that story carries on like that, through the generations. And – on this particular morning – we get reminded that even in our own time, that craziness is a craziness which can change the world.

On this particular morning, we get reminded that there are too many people living for ideas that will die… but that if you are crazy, you learn – if that’s what it takes – to die for an idea that needs to live.

For this Friday was the 48th anniversary of the murder of Bantu Stephen Biko – a man touched with just the same kind of craziness that makes people search out what is lost sheep against all the odds. A man who was so certain that the evil ideas of the apartheid government were ideas that would die that, in the short life that he lived, he demonstrated with such clarity, that crazy idea of dying for the idea of a truly free South Africa that could, as he said, “be a community of brothers and sisters jointly involved in the quest for a composite answer to the varied problems of life.”

But, back in the bad days of the 1970s, certainly for those of us watching in anguish from around the world, that idea which, for Steve Biko, was worth dying for – that idea seemed little short of impossible. It seemed as elusive as the one lost sheep in the wilderness or the lost coin in the house. And I don’t know if I would ever have been crazy enough, or saintly enough, to put my energy into going to find it – I don’t know if I would have been crazy enough to drop everything to seek out such an unlikely excuse for a party.

It has been an honour, a joy and a privilege for Canon Maggie and myself to spend some time in this country. We have been looked after and cared for with a profound sense of welcome and with grace and kindness. We have tried to engage meaningfully with the history of the country and with some of the towering, visionary, crazy people who helped bring a transformation that for so long had seemed as improbable as finding one lost sheep.

And we’ve also had some fun while we have been here. We have learned much from your gracious Dean, Fr Terry, who is, let me tell you, a most excellent tour guide. And with him, we enjoyed a lovely visit to the farm and winery at Babylonstoren. For those who have the resources to enjoy its luxury goods, it clearly is a place that offers very high quality produce, and some very fine wines – wines which are marketed successfully around the country.

And thus, as we parked up, we saw the sign pointing people to the location to which they should go if they had ordered Babylonstoren wines in advance on a ‘click and collect’ basis. ‘There you are,’ said Fr Terry, ‘everything these days is click and collect’.

But in fact – if I may gently contradict you, Father – not quite everything is click and collect.

On 18th August, 1977, Steve Biko was arrested at a police road-block near what is now Makhanda – arrested, never to be seen again by his friends or family. Arrested, and subjected to repeated severe violence, denied medical care, and left alone, shackled, naked, in a police cell. For 25 days, until his death in Pretoria, he had, in effect, vanished, like a lost sheep. He was lost in the evil, inhuman, violent and murderous wilderness of Vorster’s apartheid regime.

But he was never lost to Jesus – to the utterly crazy Jesus of whom we read in this morning’s gospel – the utterly crazy Jesus who was determined that even when Steve Biko was apparently lost to human society, beaten and bleeding in a lonely prison cell – he was not lost to God. Not lost to the God – who in the person of Christ – calls us and reminds us, crazily, never to stop searching for what is lost and precious – whatever the cost.

Because, as we are reminded so strongly in our gospel today, Jesus was not a ‘click and collect’ God of convenience and comfort – Jesus was crazy enough to journey through the wilderness, through the wilderness of this life, himself bloody and beaten in Golgotha, and – abandoned by his friends – to death on the cross. Jesus was crazy enough to do all that to search out you and me, and every precious rainbow child of God.

And that craziness is infectious, my sisters and brothers. It infected Paul. It infected Paul’s disciple who, in all likeliness wrote that reading. It infected Steve Biko, it infected and beloved Archbishop Tutu, and so many crazy Christians down the centuries, who have been for us that good example.

And so, this morning, when Jesus says to us, once more, “Which one of you – which one of you is crazy enough to go and seek out that lost sheep, whom I happen to love very very much?” Let’s make sure we can be that good example for those who come after us, let’s hope that we can raise our hands, and say, “that’s me – I’m that crazy.” Amen.

“My people have changed their glory for something that does not profit” – The Very Reverend Dominic Barrington, Dean of York

In the middle of next month, Donald Trump will return to this country for an unprecedented second state visit as the guest of the British sovereign. At the banquet that King Charles will hold in the President’s honour, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, Sir Ed Davey, will not be present. Writing in the Guardian on Wednesday https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/aug/27/ed-davey-trump-gaza-boycott-state-dinner-king-charles, Sir Ed explained that, while it goes against all his instincts to refuse an invitation from His Majesty,

“I fear we could have a situation where Trump comes to our country, is honoured with a lavish dinner at one of our finest palaces, and no one reminds him that he has the power to stop the horrifying starvation, death and captivities in Gaza. And no one uses this moment to demand that the US president picks up that phone to Netanyahu and the Qataris and does the right thing.”

Or, in the language of the prophet Jeremiah, from whom we have just heard, one might say that Sir Ed feels that the ‘glory’ of a state banquet at a royal castle hosted by the King himself is being used ‘for something that does not profit’. And thus – although it is likely that his absence may not be noticed by the US President – he will absent himself in protest, in the hope that ‘the people in Gaza are not forgotten during the pomp and ceremony’.

While I have utter sympathy with Sir Ed’s views about the awful situation in Gaza, and while I applaud the fact that he explained that he and his wife had ‘thought and prayed long and hard’ about the issue, this morning’s gospel reading forces me to observe that his strategy is a very different strategy to that taken by Jesus – at least the Jesus of whom we read in Luke’s gospel. For Jesus appeared to have no qualms about turning up to dinners hosted by people with whom he disagreed – and not just turning up, but stealing the limelight to seize an opportunity for some quite outspoken teaching.

If you dial back three chapters earlier in Luke, you’ll find Jesus at another meal hosted by a Pharisee. That episode is so shocking – at least to modern middle-class ears – that it is not included in the Church’s three-year lectionary, so the story is rarely heard on a Sunday morning. For, from the word go, this dinner party goes spectacularly wrong, with Jesus firing off insults to both host and guests – culminating in Luke’s rather understated remark that by the end of the meal the others present are feeling ‘very hostile’ towards Jesus.

And so, as the curtain rises for us this morning, a more senior figure – a leader of the Pharisees – is seeing if he can both tame this outrageous figure, and learn more clearly just how scandalous Jesus is. And while the mood around the table does not get as explosive as that in chapter eleven, Jesus is certainly not wasting another good teaching opportunity. And thus he tells what Luke refers to as a parable – but what an odd parable it is.

For parables usually speak to us in crystal clear terms about what Jesus calls the Kingdom. And usually they do so by simple and powerful similes:

Here’s a mustard seed – it’s very small but it becomes very big so that everyone could find shelter and shade – what does that tell us about God’s kingdom?

Or

A man got beaten up by bandits, and it took a despised nobody to treat him with compassion and dignity – what does that tell us about God’s kingdom?

Or

A loving father goes out of his way to care for both of his dysfunctional and badly – what does that tell us about God’s kingdom?

And so on and so on and so on….

But this morning, here in Luke chapter fourteen, we are told that this simple bit of common sense etiquette advice to help you avoid a socially awkward moment is not just a tip about how to behave in front of your elders or betters… It, too, is a parable.

It could be easy to ignore this, or regard it as a slip of the evangelist’s pen – but that would be a mistake, because Luke does not use language casually. Luke is a profound wordsmith, and if Luke is clear that Jesus intends the remarks we just heard to be understood as a parable, then that is emphatically what it is.

Because, of course, Jesus isn’t merely offering a first century equivalent of a Sunday newspaper advice column on how to avoid a social faux pas. Yet again, Jesus is doing nothing less than teaching about how things work in God’s kingdom. Jesus is saying that humility and not ostentation is at the heart of the kingdom of God – something which, manifestly, he does not see exhibited by his fellow dinner guests.

And then this conversation-cum-parable turns, pointedly, to the host – to this senior religious figure. And to the face of this influential religious leader, Jesus makes clear how he believes people are called to live out the demands of generosity, of grace, and of love.

Just over ten years ago, in Cleveland, Ohio, ten Republican hopefuls who aspired to receive that party’s nomination to run for President, took part in the first televised debate of the primary campaign. Alongside Donald Trump were a number of well-established politicians, and – as you may recall – at that point Mr Trump was considered to be an outside candidate whose campaign was bound to fail alongside the political heavy-weights running against him.

During the debate https://rollcall.com/factbase/transcript/donald-trump-first-gop-debate-august-6-2015/, Trump was accused of having financially supported – horror of horrors – liberal policies. Specifically, of liberal policies pursued by Hillary Clinton. Trump’s reply was fascinating:

“I gave to many people… I was a businessman. I give to everybody. When they call, I give. And do you know what? When I need something from them two years later, three years later, I call them, they are there for me…

…with Hillary Clinton, I said be at my wedding and she came to my wedding. You know why? She didn’t have a choice because I gave.” [My emphasis]

So – if you should find yourself invited to dinner at the White House or at Mar a Lago – understand you are there for a purpose that is utterly transactional and reciprocal – you are there to be part of a quid pro quo. Which is – of course – as even the principled Sir Ed Davey admits, the reason that President Trump will be visiting this country next month: “I argued last January that we should use the offer of a state visit – something Trump so desperately craves – as leverage to persuade him to do the right thing.”

And, lest anyone think I am painting Mr Trump in an unfair or bad light, let me add that – having explained to his Republican rivals exactly why he sometimes supported ‘liberal policies’ and just what he gained by doing so – he said, with simple and perfect clarity: “that’s a broken system” – and, about that, I think he is totally correct.

Sir Ed Davey and President Trump are not the only people whose positions on Gaza have been in the news this week, however. On Tuesday the two most senior church leaders in the Holy Land – the Latin and Greek Patriarchs of Jerusalem – issued a joint statement about the worsening situation in Gaza City https://www.lpj.org/en/news/statement-by-the-latin-patriarchate-of-jerusalem, which is where the miniscule Christian community in the Gaza Strip is to be found – and, since the war began, to be found sheltering in the church compounds of their respective churches in that city.

As you will be aware, Israel has announced that it intends fully to occupy Gaza City, and is demanding its entire population of hundreds of thousands relocate to the south of the Strip – which, to offer context, is pretty much the equivalent of ordering the populations of Leeds or of San Francisco to up sticks and move.

In response to this, Cardinal Pierbattista Pizzaballa, the Latin Patriarch, explained that for many of the sick, weak and elderly sheltering in the church compounds, an enforced flight to the south would, quite simply, ‘be nothing less than a death sentence’…. and for that reason, his clergy and nuns would ignore the demands of the Israeli military, and stay put to feed and care for their flock. To offer what one English theologian called ‘the interruptive hospitality that says no to force’…. to host meals in which there is no leverage – no quid pro quo, but, quite simply, to offer the grace and love of Christ.

Jesus offers this parable-cum-lecture to the leader of the Pharisees, because he recognises that this man is a man of substance and influence; he is man who has capacity – a capacity with which, if he so chose, he could feed the poor, the crippled, the lame and the blind. He could host a meal motivated not by the quid pro quo mentality of reciprocity, but the pro bono motivation of grace and love. But – to Jesus’ dismay – that has not been his choice. It is not how he wishes to use either his influence or his resources.

In a few minutes time, you and I will gather to be fed at the ultimate pro bono meal. The meal where the ever disruptive figure of Christ is present not as guest but as host, offering, out of grace and love nothing less than his own self, in a body broken on the Cross, and in blood spilled for the world’s salvation.

As we feast on this uniquely holy and transformative food, it is incumbent on us to ensure that we do not change the glory which it confers on us into something that, as Jeremiah so forcefully put it, ‘does not profit’.

And as Christ sends us onwards, out of the doors of this great cathedral, into a world in which there is so much suffering, need and deprivation, I pray that, as members of Christ’s own body, we will use our capacity to share God’s love without stooping to the self-interest of that ‘broken system’ that ultimately will profit nobody – least of all ourselves.

Amen.

“making peace through the blood of his cross” – The Very Reverend Dominic Barrington, Dean of York

Through Christ God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross.

Last Tuesday morning, on the last morning of the meeting of the General Synod of the Church of England here in York, Archbishop Hosam, the Anglican Archbishop in Jerusalem, addressed the General Synod and spoke about the mission and ministry of the diocese that he leads in a rather troubled part of the world.

He spoke of the 35 institutions his diocese runs – institutions principally concerned with healthcare, with education, and with hospitality. He spoke about the 28 congregations in his charge. “These,” he said, “our arms of ministry in which we show our faith in God through action and ministry. Healing the sick and teaching reconciliation with peace and justice,” he said, “is at the heart of our ministry.”

And do we know why?

Saul of Tarsus, who we also come to know as Paul, discovered in a blinding revelation, so the Acts of the Apostles relates, he discovered that in Christ all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, as we just heard read – and Saul-turned-Paul realized that this astonishing statement had implications – implications that fundamentally changed his life, changed his understanding of discipleship, of action, and of prayer.

Paul’s ministry was extraordinary and extensive and he gathered his own band of followers and disciples around him. And – probably – after his death, one of his own disciples wanted to pick up the baton, to carry on with the good work and share its mission with others. And thus this anonymous figure – in all probability – wrote to the church in Colossae, wrote the letter to the Colossians to remind them (and anyone else who might just be listening – like you and me here this morning) that Christ is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation… He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together. He is the head of the body, the church… [and] in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell.

And if that isn’t remarkable enough, through him God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross.

So, in other words, for Archbishop Hosam, and for the 35 institutions that he leads, working in those precious areas of ministry, in that troubled region. For them and for their staff, they must be Christ-like – whatever the cost – because, as the author of the letter to the Colossians makes so clear – Christ is and therefore must be at the centre of everything.

In an interview with the Church Times after his talk to the Synod, Archbishop Hosam developed the theme of what it must mean to be church in a difficult environment, what it must mean to be church in a time or war. How are we called to act as church? How do we proclaim God’s holy message? His answer was, “We are committed to reconciliation and peace-building… The ministry of presence and the ministry of resilience… We live and embody the gospel.” And he does that, and his team around him do that because, as we heard, we are now reconciled in Christ’s fleshly body through death.

And it isn’t, in a sense, just Christ’s death. It’s a call to set aside the values of human comfort and safety. We certainly know if we watch the news that the ministry of the diocese of Jerusalem comes at one hell of a cost. The Ahli Hospital – the Anglican hospital in Gaza City – that hospital has been attacked six times during the war between Hamas and Israel. Its emergency department was bombed on, of all days, Palm Sunday.

And just this past week, while Archbishop Hosam was in York, to wake us up to what is going on out there, just this past week while the Anglican archbishop was our guest, the one Roman Catholic church in Gaza City was bombed by Israel. Its priest was injured along with several others, and two people were killed – Saad Salameh, the church’s janitor, and an elderly lady called Fumayya Ayyad –whose younger brother, it just so happens, is the senior doctor, the medical director, of the Ahli Hospital in Gaza.

Years ago now, back in 2014, I visited Gaza. I was there after the last military campaign between Hamas and Israel, a campaign which at the time seemed horrifying, but really is like a children’s tea party when compared to what has happened since the terrible Hamas attacks on October 7th, 2023, and all that has followed. But I found myself, on this visit, in a war zone looking at the ruins of indiscriminate violence and bombing. It was, for somebody who has led a very innocent life in military terms, it was all very shocking. And on the last of my two nights there, having dinner with the staff of the Ahli Hospital, I found myself sitting next to this extraordinary doctor.

And Dr Maher asked me a very simple question. “Do you know,” he said, “the secret of a good life?” I didn’t dare answer, because I knew that my attempt to have a good life would sound comfortable, would sound selfish. I simply waited for him to offer me his wisdom. And he said, “It’s very simple: just make sure your neighbour has a good life.”

A remarkable statement even then from one of the tiny minority of Christians in the enclave that is Gaza – surrounded by so many Muslims, a small number of whom would actually gladly have eradicated the Christian presence. And all of them surrounded by Israel. “Make sure your neighbour has a good life,” said this doctor. And he said it, I am sure, because, In Christ God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross.

And so to hospitality. And so to that well known and well misunderstood brief little story of the two sisters, Martha and Mary. They come in a very improbable place in the gospel if you look at the action that is going on. In Luke’s gospel, Jesus takes nine chapters, from chapter 9 to chapter 18, to get from the Galilee in the north of Israel down to Jerusalem. Luke traces a journey during which Jesus teaches and preaches and performs miracles – Luke paints this journey step by step, adding to the drama that will unfold when Jesus gets to Jerusalem on what we call Palm Sunday.

And yet, because Luke has a point he needs to make for us, Luke grabs Jesus’ arrival in Bethany, at this house – Luke grabs it and yanks it chronologically completely out of place. Because Bethany is a suburb of Jerusalem. Jesus is nowhere near there. But theologically, this story comes in a very important place.

Regular listeners, as it were, might remember that last Sunday we heard the famous parable of the Good Samaritan read here in York Minster, and read in churches around the western world. That ultimate parable about action – about doing something, about being practical, about getting of your backside or getting off your horse and helping somebody. And if you come back next week, whether to the Minster or to any church in the western world, you will hear Jesus telling his disciples how to pray. Next week’s gospel begins with Jesus teaching the Lord’s Prayer. Jesus, in a sense, making sure that whatever else his followers do, they are fervent in prayer.

And in between these two so significant passages, comes, ripped out of geographical sense, comes the brief story of Jesus rolling up in the house of Martha and Mary. And this story has been subject of all sorts of interpretation, some of which have stopped us looking at what’s really going on. Martha, for instance, isn’t necessarily tied to the kitchen stove in a frantic way, because she is clearly a house-holder who has resources. Jesus didn’t rock up on his own – he had quite an entourage traveling with him.

But Martha clearly thinks that she is doing everything that counts as discipleship herself, and she has the nerve to criticize Jesus. It’s not directly Mary she’s criticizing – she’s criticizing Jesus. Because she wants to get Mary to see what is going on. It’s one of those moments when she can’t see the wood for the trees. She’s forgotten why she is busy.

But, as Colossians reminds us, you do need to be busy. We are ‘holy and blameless, says the author of Colossians, when you continue securely established and steadfast in the faith. Both of them are doing the right thing. But Martha is forgetting the right reason.

Saint Augustine, 1500 years ago, said “Martha was absorbed in the matter of how to feed the Lord; Mary was absorbed in the matter of how to be fed by the Lord. Martha was preparing a banquet for the Lord, Mary was already revelling in the banquet of the Lord.”

And it’s when we take those two sisters together – when we reconcile them – they serve as the example, together, of discipleship lived out in action and prayer. Because it’s through action and prayer together that we can be good disciples in a world where the ministry of reconciliation needs to be paramount.

At the end of his interview with the Church Times, Archbishop Hosam said, “I’m an Arab, but not Muslim . . . I am a Palestinian, but not a terrorist. And I am an Israeli, but not a Jew,”

“If,” he said, “if I can reconcile myself as both Palestinian and Israeli and Arab and Christian, surely that means that we can live together as Israelis and Palestinians?”

And that principle, that principle we see in our Scriptures this morning, applies to us and our attempts properly to be disciples. This morning we are being asked, asked by those two sisters, asked by Paul and whoever came after him that wrote to the Colossians, asked by Archbishop Hosam and Dr Maher, asked, really, by God, the very simple question: Is Christ central to us? Because, in Christ, God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross.

And so the baton gets passed down. From Jesus himself to Martha and Mary, to Saul-turned-Paul and those who followed him, so very visibly to Archbishop Hosam and Dr Maher in Gaza. The only question now, this morning, is whether Christ is central to our lives. And if he is – what are we going to do about it? Amen.

‘Let me sing for my beloved my love-song’ – The Very Reverend Dominic Barrington, Dean of York

Let me sing for my beloved my love-song…

Smadar Elhanan was the youngest of four children – the only daughter, much adored by her three elder brothers, and her parents Nurit and Rami. Her name, in Hebrew, means ‘the grape of the vine’, and is a reference to the beautiful poetry found in the Song of Solomon. In the best possible way, she was the ‘princess’ of her family, and lived a happy life in Jerusalem, until just after her 14th birthday, when two Palestinian suicide bombers detonated their bombs in West Jerusalem’s equivalent of Oxford Street, killing five people instantly, including Smadar and two of her friends of the same age.

Speaking of that terrible day, her father, Rami, says, “You find yourself running crazily through the streets, going from one police station to the next, one hospital to the next, until eventually, much later in that long accursed night, you find yourself in the morgue and [a] terrible finger is pointing right between your eyes and you see a sight that you will never, ever, be able to blot out.”

Let me sing for my beloved my love song…

In the year that Smadar was murdered, another beautiful baby girl was born in Jerusalem: Abir Aramin. Her parents, Salwa and Bassam felt the same delight that had been true once upon a time for Rami and Nurit. Fast forward ten years, and young Abir was standing with some friends outside the gates of her school in Anata, a troubled district of East Jerusalem, well known for clashes with soldiers of the IDF. And, on this most terrible of days, one such soldier deliberately shot her in the head with a rubber bullet. A day or so later, she died in hospital.

Let me sing for my beloved my love song…

It is easy, of course, to sing a love song when all is going well. But Nurit and Rami and Bassam and Salwa will not be the last parents, in the Middle East, in Ukraine and Russia, or across this broken planet, who will have to sing the heart-rending love song of grief – of a grief of separation so awful and profound that it surpasses decent imagination.

Grief of this kind is stark and ultimate. Forty years ago, 39 soccer fans were killed and hundreds more injured at Heysel stadium in Belgium. A monument erected to those who died then has inscribed upon it Auden’s poem Funeral Blues – the poem made famous from its use in Four Weddings and a Funeral, which laments so bitterly the death of a beloved:

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last for ever: I was wrong.

The stars are not wanted now: put out every one;

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun;

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood.

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

At the start of Holy Week, on the day when we have heard already in our morning worship the account of the Passion and death of Jesus, we might feel it is apt for us to be ‘in tune’ with such grief. But I want to suggest this evening, that it is not enough simply to acknowledge the pain of such grief – the pain that is inherent in the eternal story of the Passion of Christ.

For our readings tonight issue us a challenge – a challenge demanding of us that not merely do we enfold the grief of the Passion into our lives, but that we work out what God is calling us to do with it.

In other words, we must ask what it means to say that, in Auden’s terms, you should put out every star, that you should pack up the moon and dismantle the sun and pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood. What does it really mean to say that nothing now can ever come to any good?

And the answer to that question sits in that most stark and pointed parable that was our second reading. A parable that infuriated its hearers and, despite their high calling, made them bent on revenge and murder. And what a strange parable to tell… a parable that is strange, and which is almost nonsensical…

The landowner leases his vineyard to some tenants, and they default on the rent, and abuse his servants. So, eventually, he sends his son, in the hope that he will be respected by the tenants in a way in which the servants were not. But what do the tenants say? Nothing about respect or honour – instead they say This is the heir; come, let us kill him and get his inheritance.

Let us kill him and get his inheritance….? Really?

While life in the 21st Century has many differences to life in the First Century, the rules of inheritance were not that different. The tenants’ plan is nonsensical, as Jesus points out: the tenants will be put to death and the vineyard will be leased to other tenants. So what on earth are the tenants thinking? The idea would have been as ludicrous to the first audience of this parable as it is to us today. Why do the tenants think they have any chance of succeeding in this misguided, murderous scheme?

There is but one answer that can make sense of this parable – there is only one state of affairs that can underpin and account for the tenants’ seemingly bizarre behaviour – behaviour that is both murderous and suicidal. The tenants must believe that the landlord is dead.

The tenants believe the landlord is dead, and thus the inheritance is up for grabs if his son is killed as well. And given that this is a parable and not a news report, what Jesus is saying to the face of these religious leaders – who were already far from happy with his behaviour – Jesus is looking them in the eye, and saying to them, “You behave as if the God you claim to worship is dead.”

Because, if God is dead, then anything goes. And, if anything goes, then Auden is right, and nothing now can ever come to any good. Once you recognise that this underpins the logic of the tenants in the vineyard, you are hardly surprised that the scribes and the chief priests want to ‘lay hands’ on Jesus there and then.

And if we live in a world in which God is dead, then we live in a world in which the strongest and the richest and the loudest and the most bigoted will have the upper hand. And, if the world seems like that, what love song can you possibly sing then?

Isaiah’s prophecy of the vineyard is one of the most powerful passages of the Hebrew Scriptures. It is powerful in its condemnation of the behaviour of the people of Israel – the people who should have been God’s pleasant planting, but who produced bloodshed not justice. Isaiah is naming and shaming the people of God with a vision of the destruction of the city of Jerusalem and of the Temple – a prospect, symbolically, that could even be said to represent the death of God. And what love song do you dare sing then?

And by the time Jesus is telling his listeners this most powerful of parables, have no doubt that the game, as it were, is up. He knows that he is in the end game, and that the death which he has predicted not once but three times is looming. This is a man who knows that those who act as if God is dead will have no compunction whatsoever about killing him. And what love song can you dare sing then?

Those who grieve tend to make good footage for journalists. Those who grieve with real dignity make good examples for the world around them. But those who use and channel their grief, not to deny it, but to turn it into a power for good, do more than that – they change the world around them. Which is why Rami, the grieving Israeli father, and Bassam, the grieving Palestinian father, joined a remarkable organisation called The Parents’ Circle, to ensure that the tragic deaths of their daughters would not be in vain.

In this extraordinary organisation, alongside others, both Arab and Jew, who have suffered similar bereavements, they speak together as a double act, a double act of people who the world would expect to hate each other, but who, instead, claim each other as blood brothers moulded together in a love that surpasses the evil which killed their precious children. They speak together of a love-song that says that in the Holy Land and across the world, it does not have to be like this. They speak together in a way that counters those who act as if God is dead, and which demands the listener to recognise that reconciliation and peace must have the final say.

As Bassam says: ‘The year Smadar was murdered, Abir was born. But what I didn’t know when Abir was killed is that she and Smadar would keep on living. And we will not let other people steal their futures. Try shutting us up, it won’t work. [Our] grief, the power of it…is atomic. To live on in the memory of others means that you do not die’.

That is the kind of love song we should sing for those who are beloved. That is a love song that sings of God, even in a world where we it can appear that God is dead.

For Auden – well Auden would have been right. It would have been fine to put out the stars, and the moon and the sun. If loves does not last for ever, then turn them all off.

But the love song of Passiontide, the love song of Holy Week, our love song this week is a song we will sing and sing and sing – even when God will die in front of our eyes. For the love song of the washed feet and the broken bread of a Thursday night, the love song of the scorching heat and the agonized death of a Friday afternoon – the love song that gets sung as darkness covers the whole land – that love song will get sung again as the first lights of the newest dawn the world has ever known breaks on a Sunday morning.

What song will you sing for your beloved this week?

‘I am about to do a new thing; now it springs forth’ – The Very Reverend Dominic Barrington, Dean of York

Do not remember the former things, or consider the things of old. I am about to do a new thing; now it springs forth, do you not perceive it?

I was pondering this morning whether the editor of the BBC Sunday programme had been disregarding that instruction from the prophecy of Isaiah – the instruction to disregard ‘the former things’. There was a fascinating account of an important local story, as you may well have heard yourselves, or you may have read in the local press. The Bar Convent has unearthed a quite remarkable treasure: an Arma Christi scroll, dating from around 1475. A scroll – one of only eleven now of its kind extant in the modern world – that is in essence a meditation on the ‘instruments of the Passion’ – Christ’s ‘arms’, if you like. A meditation on the instruments of the Passion and of the true image of Christ, associated with Saint Veronica mopping his face on the way to his crucifixion.

On the report of this in the Sunday Programme, Sister Ann, the redoubtable Superior of the convent, remarked that, in today’s world, ‘the Passion is the last place people want to go, and yet,’ she said, ‘it is the place we need to go.’

Rather interestingly, in terms of a juxtaposition, this item on the programme was followed immediately by a report about a woman called Paula White-Cain, who is the Senior Adviser on Faith to the White House. We heard a report about a video that she has put out through her ‘Ministries’ (she’s a very successful evangelical preacher in the United States), which was talking (I thought, perhaps, rather strangely, to my ears as a Christian) about the fact that this is time for ‘God’s divine appointment with you’, because this is ‘Passover Season’.

And on offer to the faithful in Passover Season are seven ‘supernatural blessings’ that are available to us. Blessings including the assignation of a personal guardian angel, as well as also having an enemy to fight your own enemies; very predictably, giving you prosperity; taking away sickness; assurance of a long life of increase and plenty; and ensuring that it is going to be an all-round special year of blessing.

There was, of course, a slight catch to this. Quoting a verse from Exodus 23, she, and those who work with her, are very keen that you don’t appear, to use the Biblical term, ‘empty-handed’, and for donations of a minimum of at least $1,000, not only will you be in line for the seven supernatural blessings – you’ll also get a 10” Waterford Crystal cross!

I am about to do a new thing. Now it springs forth do you not perceive it?

Possibly those two extraordinary stories from the Sunday programme are old hat – medieval piety and Pentateuchal pre-Christian practice. But if we wanted to see something new ‘spring forth’ this past week, it has certainly been on offer in the world of global trade, in the big announcement of ‘Liberation Day’ by Mr Trump. He, at least in modern times, is up to something new with the introduction of tariffs, and I think it’s a pretty safe bet to say that the whole world has perceived what he’s up to.

We all saw the great scoreboard. China hits us 67% – we’re hitting back with 34%. The European Union hits us with 39% – we’re hitting back with 20%. Japan hits us with 46%, we’re hitting back with 24%. He is nothing if not confident of the rightness of his course of action. If he were to paraphrase that prophecy from Second Isaiah that we just heard read, I’m certain that he believes that he will be giving ‘drink to his chosen people’…and doing so, quite possibly, ‘so that they might declare his praise.’

I was wondering, as I watched this news unfold and I looked at that poignant reading from the gospel, what Judas might have made of the economic blessings of Mr Trump’s tariffs, let alone the supernatural blessings on offer from Paula White-Cain’s ministries. I think he might have felt that he was in good company, because Judas, of course, is the ultimate ‘transactionalist’ (if that’s a word) – the ultimate transaction-maker of the New Testament narrative: Why was this perfume not sold and the money given to the poor?

Judas’s choice, Judas’ outlook is a ‘tariff outlook’. It’s framed with the language of economic value: ‘we could have done something better with this fruit of the work of 300 days labour – we could have done something better than squander it like this.’

‘We could,’ so he claims, ‘have done something more effective with the poor’. And, of course, as the evangelist allows us to understand in a side note, the real thing that’s going on for Judas isn’t so much the economic waste of the product, as the self-interest – the question of how you personally exact the best outcome. And, just possibly, that is something we can see in more modern-day transactionalist approaches.

Certainly, Judas’ outlook is in sharp contrast to that of Mary. She is not remotely interested in economic value or in what can be obtained by a transaction. If we ought to think about ‘doing a new thing’ and making sure we ‘perceive’ it, it is, I believe, Mary who is offering us the role model that is important as we enter the season of Passiontide. For she is, quite simply, giving a gift – an extraordinary, outlandish gift, if, indeed, that perfume was worth 300 denarii. And she’s giving it without any sense of receiving anything back in return.